The Road to Decarbonising Heat

Implications for Heat Pumps

by Bean Beanland, GSHPA

In January 2018 the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) published its 2017 update to the Energy & Emissions Projections (EEP) covering UK energy demand and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions out to 2035. The report contains projections of performance against GHG targets under existing policies and reflects legally binding carbon budgets which are set for five year periods and are aimed at reducing emissions by at least 80% by 2050.

Clean Growth Strategy

The Clean Growth Strategy of October 2017 recognises the demand for massive reductions in carbon emissions to combat climate change, together with a need for cleaner air because "poor air quality remains the largest environmental risk to public health in the UK".

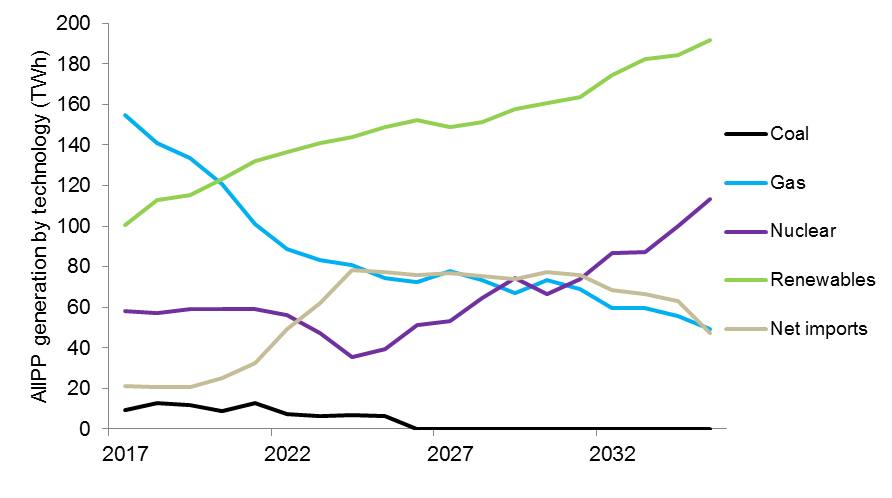

Electricity Generation by source technology — BEIS 2017 update

The document states that heating our homes, businesses and industry accounts for nearly half of all energy use in the UK and a third of our carbon emissions. Meeting the 2050 target of reducing emissions by at least 80% implies decarbonising nearly all heat in buildings. Reducing the demand for heat through energy efficiency will be a factor, but alone will not hit 2050 target.

This is the national challenge and it makes sense to start by displacing the highest carbon factor fuels first with the lowest carbon factor alternatives. From DEFRA data from 2017, the carbon factor for coal and oil both exceed 300 gCO2e/kWh at 89% efficiency. By comparison, the carbon factors of natural gas and grid electricity are 184 gCO2e/kWh and 352 gCO2e/kWh respectively.

However, the DEFRA figure for the carbon factor for grid electricity is based on historic data from 2015 which does not reflect the current trajectory: wind and solar generation capacities have since increased and coal-fired generation is being withdrawn, as set out in the BEIS graph below.

Decarbonisation of the Electricity Grid

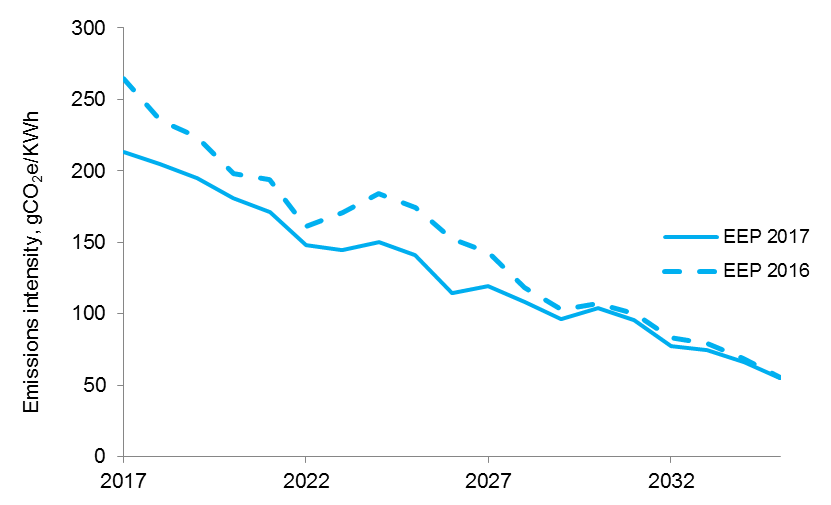

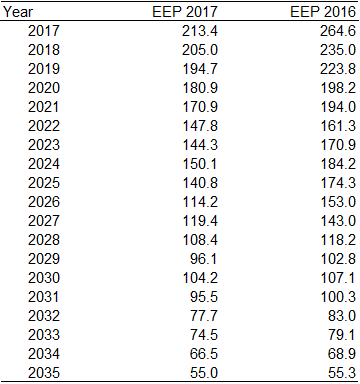

Zero carbon grid electricity remains some way off, but even SAP is likely to recognise the scale and pace of change when the outcomes of the current consultation are published. The BEIS projections suggest parity between the electricity grid and natural gas being achieved around 2020, but even this could be beaten as demonstrated in the grid emissions intensity data set and graph contained within the report and reproduced below.

GSHPs on the Grid already emit 70% less carbon than gas boilers

On that basis, a retrofit ground source heat pump with a seasonal performance factor (SPF) of 3.4 is already 70% more carbon efficient than a gas-fired boiler operating at 92% efficiency. Against an oil-fired boiler operating at 89% efficiency, the carbon saving is 80%.

For a ground source heat pump operating at an achievable SPF of 3.8 in a new build property, the carbon reduction against oil increases to 82%. Heat pumps are also zero NOx and zero particulate emitters at the point of use.

The reality is that a ground source heat pump deployed in 2018 will be progressively more carbon efficient over its anticipated life cycle of 15-25 years. The average projected grid emissions factor between now and 2031 is 150 gCO2e/kWh. Based on this figure, average emissions reductions out to 2031 would be 80% and 87% against gas- and oil-fired boilers respectively.

Grid emissions intensity in grams of CO2e/kWh — BEIS 2017 update

The Clean Growth Strategy identifies a number of short to medium term options for heat decarbonisation. These include the electrification of heat, an expansion of district heat networks, improvements to the existing boiler stock under the Boiler Plus programme, the roll-out of smart metering and investment in the development of new, low cost, low carbon technologies.

The latter could include bio-oils but OFTEC has not yet managed to bring a commercialised product to market, despite reported successful field trials in 2010, and suggests that supplies, as yet uncosted, may not be available until 2023. By contrast, heat pump technology is mature and ready to play its part immediately.

For new build, houses are already heat pump friendly by virtue of Building Regulations and extensive use of underfloor heating. However, high levels of insulation and UFH are not pre-requisites for heat pump efficacy, and the retrofitting of heat pumps to the existing housing stock can be highly successful if industry best practice is applied.

The deployment of smart meters will provide opportunities for 'demand side response', shifting electricity consumption to times when it is plentiful and cheap; equally beneficial to heat pumps and electric vehicle chargers.

However, the decarbonisation of the national grid could be a double-edged sword. The heating industry now eagerly awaits the outcome of the current SAP consultation. If SAP continues to recognise only building fabric and emissions, the default and lowest capital cost option for developers will eventually be electric panel heaters and immersions, even when displacing natural gas in the urban environment.

It will, therefore, be vital that some form of recognition is introduced to the new home building sector which addresses operational cost of ownership. It would be highly damaging for new home buyers in general, and for those in fuel poverty particularly, if the outcome of the necessary drive for low carbon emissions were to be an increase in heating and DHW costs from a current domestic gas price of less than 4p/kWh to an electricity price of 12-16p/kWh.

The only mature heating technology currently available which can deliver the required carbon emissions reductions is a ground source heat pump. Ground source heat pumps can also provide clean air health benefits, and manageable operational costs which will not be dangerously inflationary. A range of creative financial approaches to managing the capital cost of deploying ground source energy will be necessary. Various models are already being investigated which recognise the true long term value of the in-ground assets and provide for extended amortisation of the investment.

GSHPs enhance fuel security compared to reliance on imported gas

In a geopolitical world where imported energy supplies are increasingly open to risk of interruption, pulling resources back on-shore enhances fuel security and would benefit the UK balance of payments. So the decarbonisation of heat could deliver rather more than the simple headline suggests.